Let us refer to the circle centered at the origin of a Cartesian plane with radius one as the unit circle.

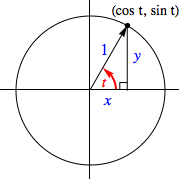

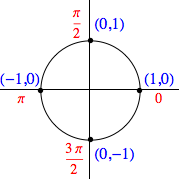

Given any real number $t$, there corresponds an angle of $t$ radians. Consider the point of intersection $P$ with coordinates $(x,y)$, of the terminal side of this angle (in standard position) with the unit circle.

Notice, if we drop a perpendicular from this point to the $x$-axis, we form a right triangle.

We have previously defined the cosine and sine functions for angles measuring between $0$ and $90^$ (i.e., between 0 and $\pi/2$ radians) to be the quotient of the adjacent side length to that of the hypotenuse, and the quotient of the opposite side length to the hypotenuse, respectively.

As the hypotenuse for our triangle has length one, it must be the case that when $0 \lt t \lt \pi/2$,

$$\cos t = x \quad \textrm < and >\quad \sin t = y$$

Seeing this, let us re-define the cosine and sine functions for any real value $t$ to be the $x$ and $y$ coordinates of the related and aforementioned point $P$.

Doing so provides a generalized version of these two functions -- one that preserves all of their previous output values for $0 \le t \le \pi/2$ while expanding their domains to now include all real values.

Let us take a moment and examine these two generalized functions before turning our attention to considering how to generalize the four remaining trigonometric functions.

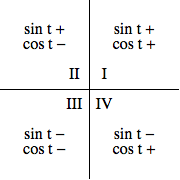

If an angle $\theta$ is an integer multiple of $\pi/2$ (i.e., $\theta = \frac

$$\begin

Of course, similar results are obtained for angles co-terminal to those above, as seen in the examples below: $$\cos \left( -\frac<3\pi> \right) = 1, \quad \sin(5\pi) = 0, \quad \cos(-6\pi) = 1, \quad \sin \left( -\frac<5\pi> \right) = -1$$

Recall that we also already know the sine and cosine values for $30^$, $45^$ and $60^$ angles (i.e., $\pi/6$, $\pi/4$, and $\pi/3$ radians, respectively). We give these again below, expressing the angle measures in radians.

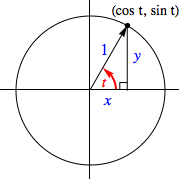

While one will find it useful to commit some of these values to memory, one need not remember all of them -- only the first two pairs. As the below graphic demonstrates, $\pi/6$ is $30^$ from the positive $x$-axis and $\pi/3$ is $30^$ from the positive $y$-axis. Consequently, the two triangles shown must be congruent. Thus, if one of the two marked points has coordinates $(x,y)$, the other must then have coordinates $(y,x)$. This in turn forces the values of the sine and cosine for $\pi/3$ to be the reverse of those for $\pi/6$ (as can be seen in the table above). Playing similar games with symmetry and triangles one can draw for various angles, we can expand our list of known sine and cosine values considerably, as the coordinates seen in the large graphic below suggest. One way to play these "symmetry games" is to realize that we can always express the values of the sine and cosine of angles whose terminal sides lie in quadrants II, III, and IV, in terms of the sine and cosine of a "reference angle" in the first quadrant, as follows:

In a manner consistent with right-triangle trigonometry, we define generalized versions of the tangent, secant, cotangent, and cosecant functions in terms of the sine and cosine functions as follows:

Note the restrictions on the domains of these other trigonometric functions. The values of $t$ excluded from their domains are those for which the denominators are equal to zero.

Since the other trigonometric functions are defined in terms of the sine and cosine, values of these other functions can easily be obtained for any $t$ for which the sine and cosine are known.